London Gallery Weekend: South London Critics Choice

The Art Newspaper by Louisa Buck

9 May 2022

Until 11 June, Castor, Enclave 1, 50 Resolution Way, Deptford, SE8 4AL

New wall-based and free-standing works combine to create an installation of distinct geographies both accentuated and partitioned by suspended veils. These map a mysterious physical and psychological underworld of both earth and body, referring to the present restless state of the earth which, due to shifts in climate and ecologies, throws up long-buried artefacts from a distant past.

What to See this London Gallery Weekend

Frieze by Salena Barry

12 May 2022

Translucent, lilac grey sheets of linen hang from the gallery ceiling like hospital curtains. We are aware of partially obscured objects in the spaces beyond them, the effect amplifying Claire Baily’s investigation into the tension between knowledge and intuition. Her freestanding sculptures have a distinctly medical quality, with clean, functional shapes and diagrammatic components. However, natural elements and processes interrupt and, perhaps, supersede these gestures toward scientific authority. Precious Cargo (2022) resembles a series of interlinking hospital stretchers, each cradling bone-like pieces of rusted metal, bone-like pieces of rusted metal. The show opens and closes with two rectangular wall-based works reminiscent of medical imagery – X-rays or microscopic photography. How Will You Remember Me and How to Build an Ocean (2022) contain murky layers of graphite that confuse as much as they clarify, reminding us that there is a depth of knowledge beneath what we can perceive.

Terra Incognita: Claire Baily excavates the unknown

Dovetail Magazine by Kate Mothes

Metaphorically, terra incognita refers to an unfamiliar place or situation. In cartography, it was historically used to denote regions that have not yet been documented, evoking surfaces, topographies, and boundaries yet to be explored. In her solo exhibition Terra Incognita at Castor Gallery, London-based artist Claire Baily confronts the dualities and paradoxes of landscape, the body, and parts unknown.

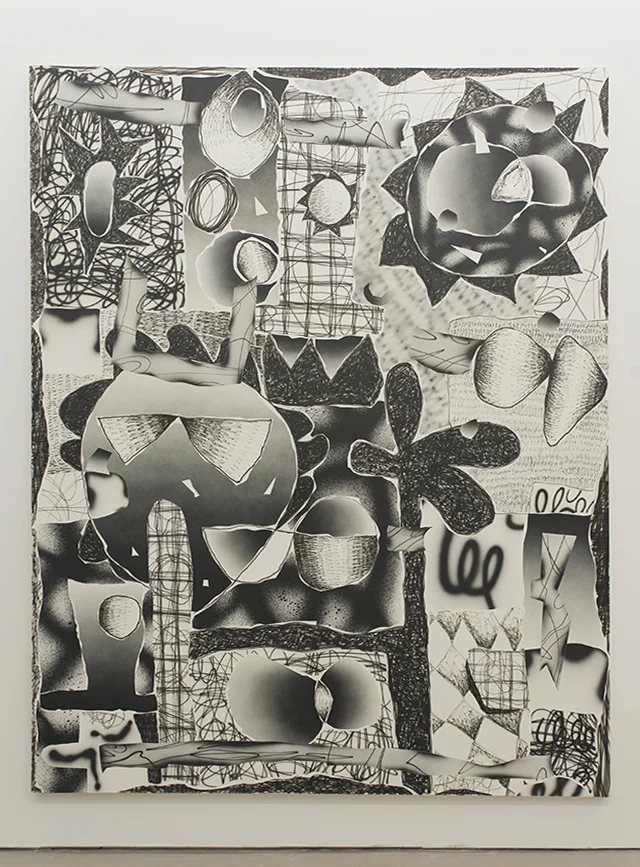

The relationship between organic and synthetic permeates Baily’s works, both in the combination of materials she chooses and in the way natural shapes converge with diagrammatic systems and geometries. Ghostly spheres overlap in the wall piece How to build an ocean, as Anna Souter writes in the accompanying essay, like bubbles, “ancient gasses trapped in archival ice cores, libraries of molecular information on the brink of being lost by a warming climate.” Nearby, in The right time and place, one feels a sense that there is a sequence of calculations or adjustments that could be input, setting the enigmatic mechanism into motion.

In the next room, You aren’t who you thought you were is a mast-like sculpture that looks stuck in suspended animation as though it could rearrange its components at any time, anchored yet prepared to set off on an unknown course. Dark resin pieces resemble fragmented pelvis bones, which appear to point in esoteric directions. Fractured and rearranged into a strange anatomy, Baily examines the experience of existing in a female body and attitudes toward the sovereignty of that body. The inner space of the womb is simultaneously vulnerable and powerful; woman as vessel is a force of nature as much as she is vulnerable to external tempests.

The largest work in the room, Precious Cargo, appears like a cross between a display platform and a conveyor belt carrying objects that resemble dowsing rods. Dowsers utilize forked branches or Y-shaped metal rods to try to divine underground waterways, gravesites, buried metals, or ley lines–straight routes along which believers argue ancient landmarks or structures were erected. Tapping into a fundamental human curiosity about why and how the universe exists and what our role is in it, the artist is akin to an archaeologist mapping out a georitual network. Partitioned off by neutral textile panels, each piece can be encountered individually, yet one only gets indistinct glimpses of other works, unable to see everything clearly at the same time.

In Rest now my melancholic heart, human hearts emerge from a clay-like surface, as if laid down carefully and buried some time ago, only now gurgling up from below lik air bubbles in a slow lava flow. The angular framework around them seems to both contain and oblige them, almost cage-like but suggestive of compartments struggling to contain the organs. Are they being held down? Organized? Dredged up?

Throughout, there is a sense of arrested motion, as if the artist has managed to slow time down to momentarily pause an elaborate process, too vast to comprehend in its entirety. At the center of the exhibition is a sense of volatility, an unsettling indication that what is hidden underneath is likely to be more immense and critical than we imagine, poised to resurface. For all our measurements, calculations, archives, and theories, how much control do we really have? Like a surreal expedition that delves into a mysterious subterrain of the heart and the earth, the artifacts uncovered here suggest that the further one digs, the further the unknowing goes.